Depending on when you were a child, an adult probably told you to finish your meal because less fortunate children were starving in India, Biafra or Ethiopia. If you grew up in a relatively high-income country as I did, this may have marked the beginning of your awareness that you were comparatively privileged.

The scale of that privilege continues to shock. When I first visited Rwanda in 2004, there was one fire engine serving a country the size of Wales or Maryland, and nine dentists for a population of ten million.

World Mental Health Day 2021

This year, World Mental Health Day highlights the yawning gap in provision between wealthy and poor nations. For instance, in the USA there are 298 psychologists for every million citizens. In the UK, the figure is 280. Meanwhile, in Rwanda there are four.

In Sierra Leone where Network for Africa also has a mental health project, there is one psychiatrist working for the army, and a clinical psychologist in private practice. There is an almost total lack of suitable medication available. Apart from 15 mental health nurses, that’s the sum of the support on offer, despite growing government awareness that mental illness and the stigma accompanying it is a massive problem. Until 2018, patients in the country’s one psychiatric hospital were kept in chains, and the 1902 Lunacy Act is still on the books. As society in high-income countries has become increasingly aware of mental health issues during the pandemic lockdowns, in Sierra Leone, demonic possession and witchcraft are still blamed, and people and their families are shunned.

Sierra Leone is the size of Ireland or Virginia, with eight million citizens. However, a civil war, Ebola and now Covid-19 have left it with at least 100,000 people with severe mental health problems. Only 2% of them have had treatment. The WHO estimates 240,000 (or one in every 33 people) has serious depression. For many, especially orphans and people whose hands were amputated by militias during the civil war, survival is only possible from begging or subsistence farming.

What is Network for Africa doing about this?

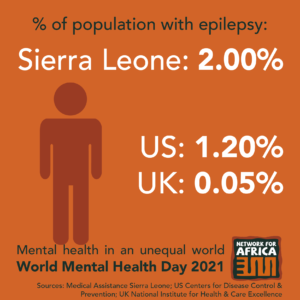

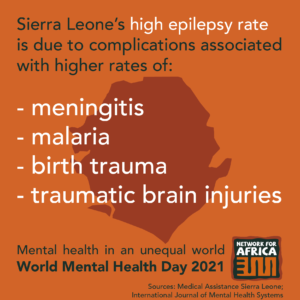

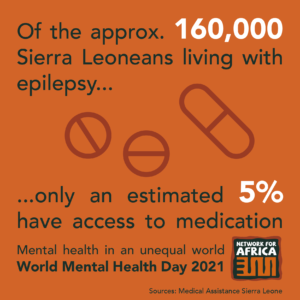

Our local partner, Conforti, works in Port Loko, a region with one of the highest rates of poverty, Ebola deaths and Ebola orphans. Whereas in the UK or USA the incidence of epilepsy is between 0.05% and 1.2%, in Sierra Leone it affects 2% of the population because of meningitis, malaria and complications during birth. Meanwhile, very few Sierra Leoneans have access to epilepsy medication.

When Ibrahim was a boy, he fell from a mango tree, hurting his head. He started having seizures which have continued throughout his life, making work impossible. We have provided counselling and medication for Ibrahim, and for the past three months he has had no seizures. He has begun working a small-scale farm and is contributing to his family’s finances. Finally, he and his relatives know he has a medical problem, not a curse from a malign force. His life has been transformed by Conforti’s breakthrough in arranging for free medication for people with epilepsy in Port Loko.

In addition, Conforti supports the existing government health system by training medical workers to understand mental health issues, as well as educating the public, countering the prejudice faced by people like Ibrahim. Conforti has established self-help groups, encouraging mutual support and giving people the confidence to start small-scale farming or businesses.

Results?

When Conforti registered people participating in the self-help groups, they found that 17% had severe anxiety. Thanks to counselling and support, that number has fallen to 0%. At the start of the year, 50% suffered often from anxiety. After counselling, the figure has halved. We salute our dedicated and hard-working partners at Conforti for their resilience throughout the pandemic. We are proud of the huge contribution they have made to bridging the gap.

To support our work in Sierra Leone, Uganda and Rwanda, please visit our webpage: www.network4africa.org/donate

Thank you.